The tendency of Canadian businesses to under-invest has been noted for decades, and the Fraser Institute reported in 2017 that investment further declined relative to that in other countries. In 2019, the C.D. Howe Institute noted that this low level of investment has been undermining the productivity of Canadian workers. This was confirmed in a follow-up report in 2021.

Every so often, I read commentators saying that we need to reduce corporate tax rates in order to help increase business investment. That is faulty logic, and I will show why.

The economics, and a graphical presentation

As I noted several years back, in Canada the net present after-tax value of a capital investment is determined after deducting the positive cash flow generated by the tax shield from the application of the capital cost allowance rules. Under the standard full-year rule, the calculation is thus:

$ NPV = I \left ( 1- \frac{td}{i+d} \right )$

where I = the gross cost of the investment, t = marginal tax rate, i = cost of capital, and d = applicable rate of capital cost allowance (CCA).

The net present value calculations also include allowances for annual operating expenditures directly connected to the project, as well as any marginal impact on working capital, but the capital investment would ordinarily be the greatest part of any proposal.

Most investments would follow the half-year rule of CCA calculation, in which case the after-tax value would be calculated thus:

$ I \left [ 1-\left (\frac{td}{i+d}\right )\left (\frac{1+\frac{1}{2}i}{1+i}\right ) \right ] $

Simple economics will confirm the truth of the following:

- the investment's tax shield should qualify for the optimal amount available under the corporate tax provisions

- any investment with a positive net present value should be accepted

- a higher cost of capital reduces the value of the tax shield

- a higher CCA rate increases the value of the tax shield

- a higher tax rate magnifies the value of the tax shield

We can display this graphically, in charts where the maximum limits used are all 50% for the cost of capital, the capital cost allowance and corporate tax rates. In the real world, we will encounter very few scenarios where any of the maximum rates would exceed these figures.

Why a 50% ceiling for the cost of capital? I went to a workshop several years back that dealt with preparing business plans for presentation to investors. Over supper later that day, the moderator told us that, in determining discounted cash flow projections, venture capital investors normally use a 40% rate for their cost of capital, while angel investors start their calculations at 50%. That weeds out all but the most attractive propositions, after which these groups will choose those which most closely align with their goals. That may be appropriate when searching for outside capital, but internal projects are not in that category. In most cases, business risks would probably justify a rate of 5%-10%.

For example, let's see what the maximum tax shield will encompass where the cost of capital is set at a moderate risk of 10%:

You can see from these charts that the corporate tax rate is plotted on a line, while the CCA rates are drawn along a curve. The second chart also demonstrates another interesting economic effect, where, at the lower values of the tax shield, an inflection point is reached beyond which an increase in the CCA rate will only have a minimal effect on the value of the tax shield. That is a point that political commentators generally fail to see.

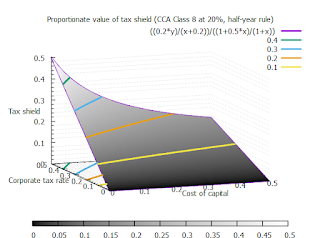

What of the other combinations of factors? Let us see what happens when the CCA rate is given, such as the 20% specified for Class 8 assets:

The cost of capital is also drawn along a curve, in the manner anticipated. Now let's see the impact where the corporate tax rate is specified (in this case, the standard federal rate of 38%):

You will notice that a 40% value line does not appear on this chart, as 38% is the maximum amount that the tax shield can reach. This also demonstrates another fascinating observation: capital cost allowance is the first building block in the tax shield, and a lower cost of capital helps to increase that value.

Some commentators have argued that tax credits could have a more pronounced effect than capital cost allowance on the investment decision. Let's revisit the first pair of charts, by inserting a hypothetical 10% tax credit. Of course, we have to adjust the tax shield calculation to ensure that the credit is deducted from the amount that would be subject to CCA:

Here, the minimum value of the tax shield is 9.09% (ie, 10%/1.1) and the initial rise in the curve is sharper, while the top is somewhat flatter, but we can still discern the diminishing value of returns as the CCA rate increases. This is something the Department of Finance should seriously study, in order to determine what the maximum value the tax shield should be generated by the capital cost allowance system, in order to nudge businesses into making more desirable choices.

Why does this matter?

For several decades now, Ottawa has sought to lower tax rates, and raise CCA rates, even though Canadian incentives have been relatively attractive compared to those of other countries. However, Canadian business investment is still relatively low. There are three factors that explain this:

- Cost of capital is risk-weighted and determined after tax - a lower tax rate will mean that the cost of capital is more expensive, which, along with higher (and possibly unnecessary) risk weightings, will reduce the expected value of the tax shield.

- A higher tax rate provides a greater incentive to shelter taxable income to be withdrawn from the business - therefore, lower rates mean that income is sheltered anyway, and also that investments are effectively more expensive to undertake. That, by the way, is also an argument against the desirability of the small business deduction.

- The CCA rate is in any case a signal as to which investments the government prefers to have businesses invest in. That intention does not necessarily coincide with what businesses see as desirable.

That last point may be more pertinent than the others.

A 2015 study by Statistics Canada revealed several reasons why Canadian businesses chose not to invest in advanced technologies. For manufacturing enterprises in particular, the reasons were:

| Reason for not investing |

Percent of respondents |

| Not applicable to the enterprise's activities |

50.1 |

| Investment not necessary for continuing operations |

32.9 |

| High cost of advanced technologies |

16.9 |

| Not convinced of economic benefit |

14.3 |

| Lack of technical skills required to support this type of investment |

7.9 |

| Difficulty in obtaining financing |

6.0 |

| Lack of information regarding advanced technology |

5.3 |

| Capital expenditures made more than three years ago |

2.4 |

| Use of technology-sharing agreements or contracting for advanced technology needs |

1.0 |

| Decisions made elsewhere in the organization and not in the enterprise itself |

0.8 |

| Other reason for not investing |

1.7 |

It's obvious that some respondents gave multiple reasons, but the main gist is apparent. When almost two-thirds of respondents say that advanced technology is either not applicable or of no convincing benefit, you know that there is a fundamental issue out there. Even the Bank of Canada has noted that

this under-investment exceeds even that predicted in its models.

Therefore, given the inconsequential effects of current tax policy on capital investments, what other levers can the government pull in order to push businesses to make desirable investments? There are several, and they all require work (ie, extensive audit and review) in order to be effective:

- regulatory requirements and sanctions

- industrial policy for providing economic incentives for preferred goals

- higher corporate tax rates

This past week,

The Economist devoted

a special section on this very matter, and I will not repeat what it says, It is well worth reading, in order to note what to watch out for and avoid in order to be worth pursuing.

No comments:

Post a Comment